The following is a transcript of a 2008 Compassionate Boldness lecture by Ronald V. Huggins.

My name is Ron Huggins. I teach at Salt Lake Theological Seminary; historical and theological studies is my area. I’m glad to be with you tonight. I’m glad to see you all here tonight. Thank you for coming.

I’m sad to report that most Christians don’t understand very much about the creeds or how they came to be. As a result, they are usually not adequately prepared to help people who have been misled by the misrepresentations of LDS leaders, scholars, and apologists.

Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, once said, “We believe the Bible and all other sects profess to believe their interpretations of the Bible and their creeds.”

Current Mormons often say the same sort of things. Mormon scholar and apologist Stephen E. Robinson, for example, in the dialogue book he did with evangelical Craig L. Blomberg back in 1997, asserted,

“There isn’t a single verse of the Bible that I do not personally accept and believe, although I do reject the interpretive straitjacket imposed on the Bible by the Hellenized church after the apostles passed from the scene.”

Or, again, Robert L. Millet, in his dialogue book with Evangelical Gerald R. McDermott:

“Mormons… say they believe every word of the New Testament but do not find those words suggesting what the orthodox church has conceived in its classic Trinitarian formulas.”

But I will argue that what Smith, Robinson, and Millet say is simply untrue. Despite the fact that I hold all creeds to be ultimately subordinate to scripture, it seems to me that quite a good case can be made for regarding, for example, the Nicene Creed as far more faithful to the Biblical teaching than the Mormon doctrine of God in its various historic expressions.

The Nicene Creed

So tonight, let’s have a look at the Nicene Creed. Here it is in the form it originally took in the year 325 AD:

“We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of all things visible and invisible.

And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten of the Father, Only Begotten, that is, from the essence of the Father, God of God, Light of Light, true God from true God, begotten not made, of one essence with the Father… by whom all things were made, both things in heaven and things on earth; who was made man, suffered, and rose again the third day, ascended into heaven, and is coming to judge the living and the dead.

And in the Holy Spirit.”

In my discussion, I want to address the first two articles separately. Obviously, [with] the third one hasn’t seen much development at this stage.

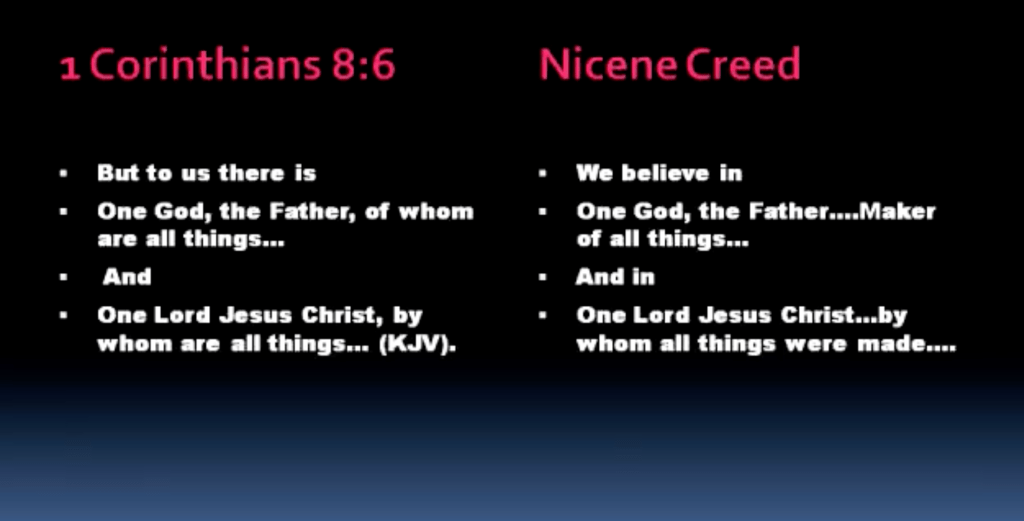

Before I proceed, I’d like to draw your attention to the fact that these two articles both echo the language and content of 1 Corinthians 8:6. Unless otherwise noted, all my quotations come from the King James Version since that is the Mormons’ official version. You see here: “But to us, there is one God, the Father, of whom are all things, and one Lord Jesus Christ, by whom are all things.” And we have this one God, one Lord thing going on in the Nicene Creed as well.

The three-article Creed grew up around the language of the Great Commission in Matthew 28:19: “Go ye therefore and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost.” This basically became the foundation for teaching what that meant before you were baptized. Then you would confess as you were being baptized.

We can see this in a traditional baptismal liturgy used at Rome and described by the writer Hippolytus around 200 AD. It is a threefold baptism with a question asked before each dunk. And the person being dunked was in no clothes; they were in their Adamic uniform.

Here are the three questions:

- Do you believe in God the Father Almighty?

- Do you believe in Jesus Christ, the Son of God, who was born of the Virgin Mary, crucified under Pontius Pilate, and so on? (You recognize the familiar language of the Apostles’ Creed and other Creeds.)

- Do you believe in the Holy Ghost, the holy church, and the resurrection of the flesh?

After each of the three questions, the person would answer “Credo” (I believe), and then they would be submerged.

The First Article

Let’s move on to the first article: “We believe in one God, God the Father Almighty, maker of all things visible and invisible.” In several other Creeds and creedal formulas of the 4th century and before, the first article is shorter than it is in the Nicene Creed, agreeing in form with the question in the Roman baptismal liturgy: “We (I) believe in God the Father Almighty.” This is what we find, for example, in what’s called the Old Roman Creed and in the Creed of Arius, the great 4th-century heretic.

The Nicene Creed derived its reference to the Father’s being “maker of all things visible and invisible” from the Creed that was used as its pattern, the Creed of the Church of Caesarea in Palestine. Many Creeds and creedal statements from around this time and even considerably earlier also include a similar reference to God as the creator of all.

The representation of God as the maker of all things visible and invisible in the first article of the Creed of the Church of Caesarea, which we can also refer to as the Caesarean Creed, comes as an echo of Colossians 1:16-17:

“For by him were all things created, that are in heaven, and that are in earth, visible and invisible, whether they be thrones, or dominions, or principalities, or powers: all things were created by him, and for him. And he is before all things, and by him all things consist.”

The Caesarean Creed also cites in its second article Colossians 1:15, the line immediately preceding this passage, which refers to Jesus as “the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of every creature.” But the Nicene Creed replaced that for reasons I’ll explain later but kept the echo in the first article.

There are three issues of special interest in relation to this first article that we want to look at tonight:

- Its background in Jewish monotheism, which will be more conveniently dealt with a little later.

- Its description of God as Almighty, which comes from the Greek word “παντοκράτωρ” and was translated into the Latin “omnipotens,” from which we get the word “omnipotent”.

- The relation of the reference to God being the maker of all things visible and invisible to the doctrine of creation ex nihilo.

Let’s look at the last two in turn.

The Omnipotence of God

When the early Christians thought of God the Father as omnipotent, they had in mind that he held all power that existed. Naturally, the Christian understanding cannot be applied to the Mormon God, who, at least in his traditional description, was a relative latecomer to divine authority in the history of the universe, who holds limited dominion over his own smaller universe, which is a a corner of the larger universe, as a sort of tribal deity that reigns only over his progeny but not over the progeny of those infinite number of other gods that preceded him or surrounded him in neighboring universes.

So naturally, when the Mormons use the term, they always need to qualify it. The Mormon God is omnipotent over the realm of which he rules, which Christians would view as another way of saying that he is not omnipotent. So then why do the Mormons continue to use the term? My own view is that it’s because Joseph Smith used it in the Book of Mormon, where Jesus is referred to as the “Lord omnipotent” or the “Lord God omnipotent” on several occasions in Mosiah 3 and 5. And so, as long as they hold to the Book of Mormon, they are stuck with the word.

When Joseph wrote the Book of Mormon, he was a very strict monotheist, a position he jettisoned in favor of polytheism or henotheism—in other words, the worship of one God among many—before he had done with writing his last scriptures or giving his last revelations. As a result, the Mormons find themselves in the difficult position of having to try to harmonize the essentially different theologies Joseph came up with along the way. In consequence, when they try to correlate their own current pluralistic theology with the baldly stated monotheistic God of the Book of Mormon, they are inevitably forced to resort to making caveats of radical diminution or devaluation.

Yes, God is eternal, but that does not mean that he was eternally God. He is omnipotent, but only in his own realm or universe. God knows all things, but only because at some point he was brought up to speed on the things he didn’t know before. God is from everlasting to everlasting, but everlasting can have a beginning and an end. Everyone is a literal son and daughter of God, but there are other everyones in other places who are literal sons and daughters of other gods.

Those unfamiliar with this aspect of Mormon teaching may be helped by the following remarks from Mormon scholar Robert J. Matthews in a 1998 book that Robert L. Millet edited with Kent P. Jackson. Under the subheading “The Plan of Salvation Never Changes,” Matthews writes,

“Elder Orson Pratt expressed his understanding of the antiquity and unchangeableness of the plan as follows: ‘The dealing of God towards his children… is a pattern after which all other worlds are dealt with. The creation, fall, and redemption of all future worlds with their inhabitants will be upon the same general plan. The Father of our spirits has only been doing what his progenitors did before him… The same plan of redemption is carried out by which more ancient worlds have been redeemed.'”

Matthews continues,

“The reason Elder Pratt’s statement makes doctrinal sense is because the plan of God is perfect, and perfection is unchanging. If the plan of redemption varied from time to time, from world to world, or person to person, men would be saved by different means, and salvation would have its bargain days.”

God is the “maker of all things visible and invisible.”

One of the things that might help us understand the significance of the Creed is that the early Christians did not, as do current Mormons, labor under any necessity of separating words from their meanings. Thus, when they read in Scripture that God had created all things visible and invisible through Christ, they didn’t have to say, “Well, all things only means some things, the things God organized out of pre-existent matter while putting together his own universe. Other gods in other places having similarly organized their own universes in the same way.” And when in John 1:3 it says of Jesus that, “All things were made by him, and without him was not one thing made,” the early Christians understood the gospel author to mean by “all things” everything, and by “not anything” nothing.

Part of the reason for Mormonism’s difficulty in taking the words of Scripture at face value in these cases is its idea that God did not create the world but organized it out of pre-existent matter. We see this in the Book of Abraham 4:1 [and] Doctrine and Covenants 93. In this, Mormon theology stands closer to Greek philosophy, particularly Platonism, than to Judaism or Christianity. Like the Mormons, Plato conceived of creation as imposing shape and form on pre-existent matter, as the idea of a chair might be imposed on a pile of pieces of wood.

In his book “Timaeus,” Plato has his main character explain the nature of this pre-existent matter, which is called “the molding stuff for everything.” He uses the analogy of gold:

“Now imagine,” he says, “that a man were to model all possible figures out of gold and were then to proceed without cessation to remodel each of these into every other. Then if someone were to point to one and ask, ‘What is it?”, by far the safest reply in point of truth would be to say that it is gold. But as for the triangle or other figures that were formed in it, one should never describe them as being, seeing that they change even while one is mentioning them.”

He further stresses that this pre-existent stuff is formless:

“It is right,” he says, “that the substance which is to receive within itself all kinds of shapes should be devoid of any form of its own, just as with fragrant ointments, men make the liquids that are to receive the odors as odorless as possible.”

And so we see a similarity there, which Joseph Smith gets in touch with in the Book of Abraham, possibly… well, we won’t speculate on where he derives this from.

The First Article and Heresy

The statement in the first article of the Nicene Creed about God being the creator of all things visible and invisible can be thought to have arisen to serve early Christianity’s interest in countering certain second-century heresies such as Marcionism, or more generally, gnosticism.

Marcion, who was active in Rome in the middle of the second century, said that the creator of the world was a different God than the God of Jesus. The fact that he created the material world meant that he was actually positively evil.

In the same way, many of the Gnostics believed the God of the Old Testament was a stupid being whom they called the Demiurge, who, being unaware of the fact that there were many higher divine powers and beings above him, imagined himself to be the only true God and therefore regularly made idiotic remarks like the one in Isaiah 43:10, “Before me no God was formed, nor will there be one after me,” or Isaiah 44:6, “I am the first and the last; beside me, there is no God,” or again, Isaiah 44:8, “Is there a god besides me? Yes, there is no God; I know not any.”

The speaker in these passages is Jehovah, as is seen by the use of “LORD” in all capitals in most English translations, including the LDS edition of the King James. So according to current LDS theology, that would be Jesus. Jesus is Jehovah. It would be interesting, if that were the case, that Jesus would say such things, knowing that he had a Heavenly Father and that his Heavenly Father stood in a long line of gods.

In any case, the early Christians felt it was important to affirm the identity of the creator of the world and the Father of Jesus as the creator of all things. The question we just asked, “How could Jesus say that no God was formed before him if he knew about the Father?” could, if you think about it, be turned back on us by asking, “Well then, why would the Father say such a thing if all the time he knew about Jesus the Son?” It’s a good question, but for now, I have to leave it hanging so I can lay a little groundwork for our discussion of the second article.

The key thing I need to focus on in the second article of the Nicene Creed are places where it modifies material taken over from the underlying Creed of Caesarea. Eusebius took the Creed of Caesarea to the Council and read it, and it became the basis of discussion and modification. You’ll note some of the statements were rearranged from the order the Creed of Caesarea had it. I’ve just rearranged those in the order that the Nicene Creed ends up with.

It seems clear that each of the changes seems to reflect the reason for which the Council was convened, which was to counter Arianism, which was named for Arius of Alexandria. Of particular significance is the dropping in the Nicene Creed of the reference to Jesus being begotten before all ages and to his being firstborn of all creation.

The followers of Arius had a little phrase they used to describe what they thought of Jesus: “There was when he was not.” They taught that he was a creature, albeit a very exalted one, and that therefore there must have been a “time”—if time is the right word—before which he existed. Although in Scripture itself, Jesus is referred to as the firstborn of every creature, and Arians could construe that to mean that he was the first created being, Orthodox Christians have argued that the term “firstborn” in context refers to his preeminence over all created things, not his being one of them. This, they feel, is made quite clear in what immediately followed in Colossians, and I just read it.

We don’t have much time to enter into the Arian controversy in our context, but here is the passage:

“For by him were all things created, that are in heaven, and that are in earth, visible and invisible, whether they be thrones or dominions or principalities or powers: all things were created by him and for him. He is before all things, and by him all things consist. He is the head of the body, the church: who is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead; that in all things he might have the preeminence.”

He is the firstborn of all creation; he is the firstborn of the dead. It’s good to remember at this point that whichever way we go with the Arian or the orthodox reading, we’re dealing with a much more exalted view of Christ than current Mormonism, where nothing as comprehensive can be said about him. As we said, in each case, we would need to replace the “alls” with “somes.”

In fact, I did that just to give a feel: “For by him some things were created, everything that is in this heaven and in these earths, visible and invisible… some principalities… powers.” But according to Colossians, if there are thrones, Jesus is behind and before them. They all consist in him. If there are dominions, if there are gods, Jesus is at their head; he’s not a latecomer.

But let’s get back to the topic. Positively, the Council Fathers sought to clarify that Jesus was not created, and the way they did it was by giving more specificity to the word “only begotten.”

You’ll see on the sheet there that you have the comparison. And you can see the differences: “only begotten Son,” “only begotten of the Father,” that is, “from the being (ousia) of the Father.”

He is from the being of the Father. He is more than the product of the Father’s will or command, his fiat. He is not a creation; he derives his being from the Father. That’s what it means to be a Son as opposed to a created thing. You have a son; you make a thing. That’s the essential distinction they were trying to make.

Homoousios

This is made more clearly below, where it says that he was “begotten, not made, of one being (homoousios) with the Father.” Notice the similarity between the word “homoousios” here (one being) and “ousia” (being) above.

Mormons delight in targeting this word “homoousios” in the Creed as making a serious departure from the Bible into the realm of philosophical speculation. I have never read a Mormon writer who notices that “homoousios” echoes the earlier use of “ousia”—there may be one; I just haven’t noticed it—or that the introduction of both words can be seen to represent a fairly modest clarification, namely that Jesus was the Son, not the creature, of the Father, an idea that Mormons agree with.

Indeed, I sometimes wonder why Mormons, in the midst of attacking the word, have never paused long enough to notice that their own doctrine might be able to apply “homoousios” in a much more comprehensive way by using it to describe how all humans are of the same species as God. Mormons regularly say that we’re all of the same species as God. Why not simply take “homoousios” to refer to that in the context of plurality? Were they to do so, it might actually bring more clarity to Christian-Mormon discussion by setting out in sharper relief the difference between the Biblical and the Mormon meaning of the term “only begotten.”

Current Mormon teaching on the meaning of “only begotten” is well expressed in the LDS-published “Gospel Principles”:

“Jesus is the only person on Earth to be born of a mortal mother and an immortal father. That is why he is called the only begotten Son.”

In other words, we are all begotten of God in Mormon theology in the sense of being born as spirit children to Heavenly Parents. But Jesus is special in that besides that, he obtained his body in an unusual way through the physical union of God the Father and one of his spirit daughters, Mary of Nazareth.

But here again, we have what would be considered a major devaluation of the real uniqueness of the term “only begotten” from the perspective not only of the early Christians but also of their own scriptures and founding prophet, which again stood nearer to the Biblical and Christian position than does current Mormon teaching.

We see this perhaps most clearly in the Pearl of Great Price, Moses 5:9, and here is the quote: “I am the only begotten of the Father from the beginning, henceforth and forever.” If you read that opening passage in the Book of Moses, which is supposed to be the opening chapters of Genesis restored, you’ll see that the Only Begotten is there, and he is being spoken with, and God creates man in his—the only begotten’s—image, whereas later, now he becomes the only begotten at his birth.

In the Bible, the term when applied to Jesus is unique to the Gospel of John, who never uses it in relation to Jesus’s being born according to the flesh from the Father. Indeed, when we think of the great affirmation of John 3:16, “For God so loved the world that He [sent] His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him should not perish but have everlasting life,” it seems cheapened somehow if the term simply points to the source of God’s special love for Jesus in the fact that he is directly derived from his Father’s flesh, while his other children are in some sense once removed from God’s love only in the fact that they got their bodies in a more ordinary way.

Joseph’s own use of “only begotten” owes a lot to John 1:14, and you’ll see this in your handout there.

For example, in the Book of Mormon, where he’s supposed to be translating reformed Egyptian, we find the language of John 1:14 in Alma 5:48: “The Son, the only begotten of the Father, full of grace and mercy and truth.” Alma 9:26: “The glory of the Only Begotten of the Father, full of grace, equity, and truth…” Alma 13:9: “The only begotten of the Father… who is full of grace, equity, and truth.”

In the Inspired Version, where Joseph is supposed to be supernaturally restoring the Hebrew text of Genesis, we find John 1:14 in the mouth of God speaking to Moses [1:6]: “Mine only begotten is and shall be the Savior, for he is full of grace and truth.” Moses 1:32: “My only begotten, who is full of grace and truth.” Moses 5:7: “The only begotten of the Father, which is full of grace and truth.”

Joseph likes this word, and he does this a lot with individual little scriptural phrases in all his revelational statements.

In the Doctrine and Covenants, where he’s supposed to be giving us a rationally restored passage from John the Baptist, we find it again:

“And I, John, bear record that I beheld his glory as of the glory of the only begotten of the Father, full of grace and truth, even the spirit of truth, which came and dwelt in the flesh and dwelt among us.”

The Christian definition of “only begotten” involves another fact that needs to be taken into account. Early Christianity, like Judaism before it, was a monotheistic religion. The Creed of Judaism, which already by the time of Jesus was in the mezuzah or mezuzot that Jews attached to their doorposts and the phylacteries that they bound on their arms and foreheads.

It was pronounced by Jews in the morning and evening. Throughout the ages, the favored words on the lips of Jewish martyrs, the first subject discussed beginning with the very first line of the Jewish Mishnah, believed on and confessed by Jesus at the beginning of his answer about which was the greatest commandment, thus binding the affirmation on the consciences of all those who would claim to be his followers forever after, the Creed of Judaism, the great Shema:

“Hear, O Israel, the LORD our God, the LORD is one” (Deuteronomy 6:4, Mark 12:29-30).

Consequently, for the early Christians on either side of the Nicene debate, however you explain the relationship of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, it all had to add up to one. The late words of Joseph Smith, claiming that the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost constitute three distinct personages and three Gods, which current Mormonism often embraces, simply would not have done.

Arius and his followers tried to solve the problem by saying, “Yes, there’s only one God, and it’s the Father; Jesus is not God.”

Other early Christians, called modalists, went in the direction Joseph Smith takes in the Book of Mormon, saying that even though there are three persons called God in the New Testament, really behind them all there’s only this one person, somehow wearing different masks or in different projections or different expansions. We see this most clearly in Abinadi’s speech in the Book of Mormon:

“God himself shall come down among the children of men and shall redeem his people; and because he dwelleth in flesh, he shall be called the Son of God: and having subjected the flesh to the will of the Father, being the Father and the Son; the Father, because he was conceived by the power of God, and the Son because of the flesh—thus becoming the Father and the Son: and they are one God, yea, the very Eternal Father of heaven and of earth” (Mosiah 15:1-4, italics added).

In the Book of Mormon, in other words, Jesus is not called the Son because he got his physical body from God; he’s called the Son because he is the physical body of God.

But when all is said and done, there is simply too much going on in the Bible to support Arianism, ancient styles of modalism, Book of Mormon modalism, or present-day LDS pluralistic polytheism. Since these meetings are aimed at helping people interact with current Mormonism, I will try to make a case for what I have just said by testing the current Mormon teaching against the biblical data.

According to current Mormonism, Jesus is Jehovah, the God of the Old Testament, and Elohim is God the Father. A document called “The Living Christ: The Testimony of the Apostles,” signed by the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles on January 1, 2000, puts it this way:

“When one speaks of God, it is generally the Father who is referred to; that is, Elohim. All mankind are His children. The personage known as Jehovah in Old Testament times, and who is usually identified in the Old Testament as ‘LORD’ (in capital letters) [if you have ever looked at your Bible and wondered why ‘LORD’ was sometimes capitalized and sometimes not, that’s why, and it goes back to the King James at least], is the Son known as Jesus Christ, who is also a God.”

I do not know when the LDS Church began teaching this. It does not, in any case, appear to have been the view of the later Joseph Smith, as is seen from a prayer of the prophet recorded in the History of the Church for August 22, 1842, where Joseph identifies Jehovah with Elohim and both with the Father of Jesus Christ:

“Thou eternal, omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent Jehovah—God—Thou Eloheim… look down upon Thy servant Joseph at this time; and let faith on the name of Thy Son Jesus Christ… be conferred upon him.”

So we find Joseph using Jehovah and Elohim both in reference to the Father.

Our task, however, is to evaluate the current Father=Elohim, Son=Jehovah in light of scripture, and when we do that, we see that it makes an awkward fit.

In the first place, there’s no doubt, in agreement with the current Mormon view, that scripture does separate the Father and the Son in some sense into distinct persons.

The most important passage in this regard relates to the Garden of Gethsemane, where, as an example, in Matthew 26:39, Jesus falls on his face and prays, “Father, if it is possible, let this cup of death pass from me, but not my will, but your will be done.” This shows not only that the Father and the Son have different wills, but also that the Son is submitting his will to his Father.

There was a time when I was a modalist, and it was this passage that really shook loose that idea.

Also, from John 8:58, when Jesus says to the Jews, “Before Abraham was, I am,” and they take up rocks to kill him, we know that Jesus identifies himself with the great “I AM” on Sinai in Exodus 3:14. That he is Jehovah, and the Jewish people who listened to him recognized themselves. That he was committing blasphemy by identifying himself with Jehovah.

Yet, at the same time, as so often happens in the Bible, we have a tension that cause us to be driven to the Trinitarian doctrine, which is not done justice to by simply saying, “Well, Jehovah is the Son, and Elohim is the Father.” We see this most clearly in two prophetic passages from the Old Testament.

Psalm 22

The first is Psalm 22, which the writers of the New Testament understood to be describing the suffering of Jesus, and whose opening line Jesus himself quotes on the cross: “My God, my God, why hast Thou forsaken me?” Psalm 22:18 says, “They part my garments among them, and cast lots upon my vestures,” a statement the Gospel of John says is fulfilled when the soldiers cast lots for Jesus’s clothing in John 19:24. And then there’s a remarkable statement in Psalm 22:16: “They pierced my hands and my feet.”

Once we understand that Psalm 22 is a prophetic description of the suffering of Jesus, we are able to see other things that are helpful as well. The New Testament tells us that Jesus was mocked as he hung on the cross. These mockers appear in Psalm 22:7-8, and what do they say? “He trusted in Jehovah” (you’ll see “LORD” in capital letters in your Bibles), “let [Jehovah] deliver him.” Then in Psalm 22:19, in case those guys got it wrong, Jesus himself prays, “Be not far from me, O Jehovah, O my strength, haste to help me.” In this passage, then, Jesus is not Jehovah; the Father is.

Psalm 110

The second passage is Psalm 110:1. In Hebrews 1:13, where the greatness of the Son is being contrasted to that of the angels, the author says, “But to which of the angels said he at any time, ‘Sit at my right hand until I make thine enemies thy footstool?'” If you read the passage in context, you’ll see that the implication is that the Father is the one speaking and saying these things to the Son, Jesus.

So now, in Psalm 110:1, we read, “The LORD said to my Lord, ‘Sit at my right hand.'” Notice again the capitals on the first “LORD,” cluing us into the fact that the underlying Hebrew reads, “Jehovah said to my Lord, ‘Sit at my right hand.'” Who sits at the right hand of the Father? Not Jehovah—Jesus.

In reality, the current Mormon arrangement is simply not representative of the Biblical evidence. The name Jehovah is the personal covenant name of the God of Israel, while Elohim is simply a word meaning “God” or “gods.” But the real interesting implication of this practice of splitting Jehovah and Elohim into two different gods is the fact that if that were so, the Bible would clearly command us to worship only Jesus, but not the Father.

We see this, for example, in Deuteronomy 6:13, which Jesus quotes at the devil in the wilderness: “Thus saith Jesus unto him, ‘Get thee hence, Satan, for it is written, Thou shalt worship the LORD thy God, and him only shalt thou serve.'” The LORD in the passage in Exodus is Jehovah.

And then finally, in the first commandment of Exodus 20:2-3: “I am Jehovah thy God; thou shalt have no other gods before me.”

So then, what’s the answer to the claims of Smith, Robinson, and Millet put forward at the beginning, that Mormons simply follow the Bible while Christians follow their Creeds off into philosophical speculation? I fear the truth is the reverse.

One of the most tragic things in my mind that was accomplished by Joseph Smith is his ability to undermine faith and confidence in the Bible. Shawn McCraney expresses the situation well when he writes,

“The greatest disservice Joseph Smith did to members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, past, present, and future, was his subtle attack on the authority and authenticity of the Bible. This act has led hundreds of thousands of innocent people to distrust and even mock the holy word of God. In spite of Joseph Smith’s best intentions, I see him as having committed a grave spiritual and ecclesiastical crime.”

The same attack on scripture continues in present-day Mormonism, as is seen in the following little section of “Helps for Family Home Evening” that appeared in connection with an article entitled “Plain and Precious Truths Restored” by Clyde J. Williams in the October 2006 Ensign. I took the little clip of what it actually says there:

“Make a copy for each member of a simple recipe for a treat that everyone enjoys. Then make a second copy of the recipe with key ingredients and cooking processes missing. [You see what it is; we’re making cookies. Well, we’re going to leave out the sugar, and we’re going to leave out the chocolate chips.] Discuss the differences in the recipes and the problems that arise when essential information is missing. Compare this to what the author shows happened to the scriptures when plain and precious truths were removed.”

The fact that the above exercise is aimed at leading little children to distrust the Bible and place their trust instead in the shifting speculations and clumsy religious forgeries of men is very, very sobering and reminds us of Jesus’ solemn warning in Matthew 18:6:

“But whoso shall offend one of these little ones which believe in me, it were better for him that a millstone were hanged around his neck, and that he were drowned in the depth of the sea.”

Jesus is always very visual in what he says.

Now, of course, no loving parent wants to lead their children astray. The parents who use this little exercise didn’t want to deceive their children; they only did it because they believed it themselves. And what about the author of this little exercise about the recipe? Again, he or she would have never conceived of it in bad faith.

Even the present-day Mormon apostles and prophets are what they are because of the high level of efficiency with which they have been indoctrinated into their system. As Paul says in 2 Timothy 3:13, “Deceiving and being deceived.”

As the Apostle Paul says, “Our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world, and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms” (Ephesians 6:12). But Christ is greater than all. It is he who has the power to open their eyes, turn them from darkness to light, from the power of Satan to God, so that they may receive forgiveness of sins and a place among those who are sanctified by faith in him, as it says in Acts 26:18, just as he’s done with every one of us who have come to know him already. Thank you.